by Winston Brown

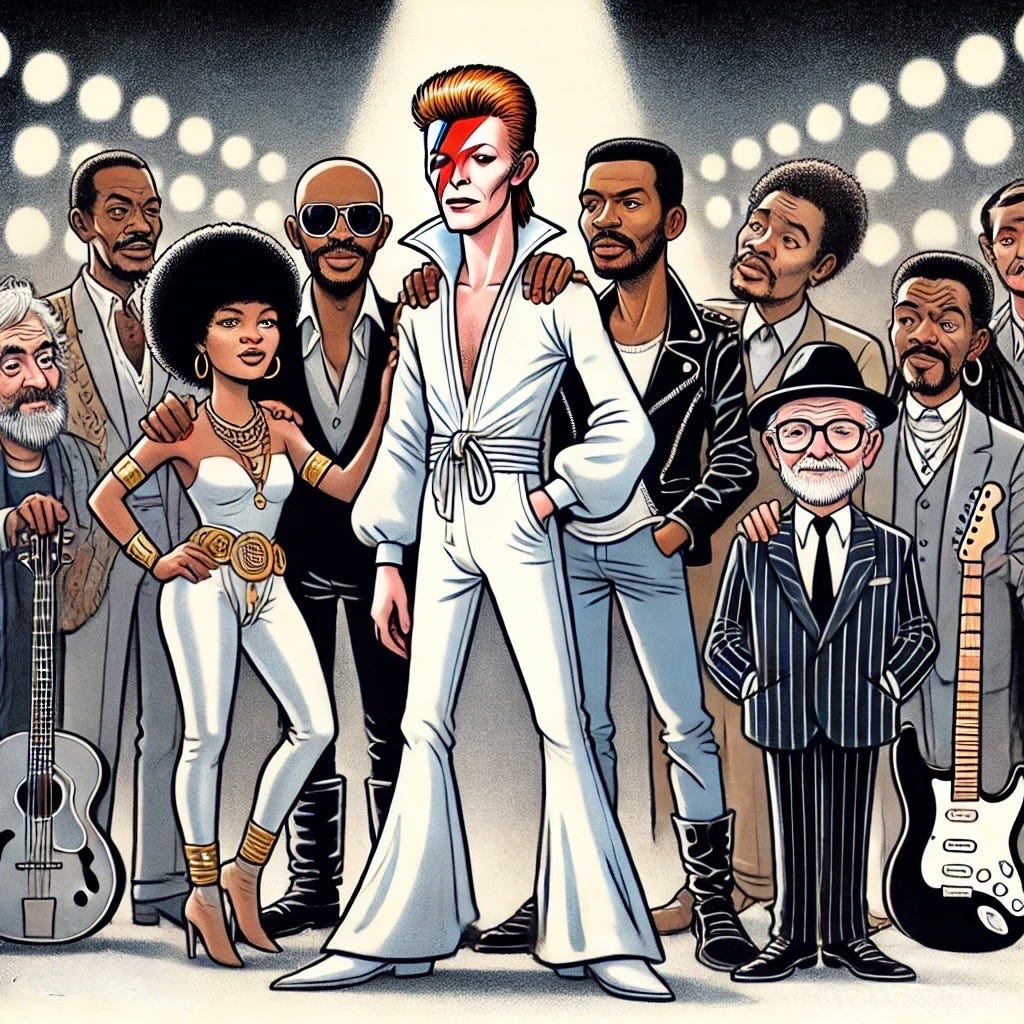

Let’s get one thing straight—David Bowie wasn’t some charity case for Black music. No, sah. The man understood, respected, and collaborated with Black musicians in a way that puts most of his era’s rock gods to shame. While some of his contemporaries were busy “borrowing” Black sounds and passing them off as their own, Bowie was in the trenches, working alongside the greats and making sure they got their flowers. And in a world where white artists have a nasty habit of taking without giving back, the man deserves credit where it’s due.

Now, I know what you’re thinking. Winston, why are you, a South London man with a decolonised mind and a well-documented distrust of Babylon, bigging up a white rock star?Well, because when someone actually does the right thing, you have to acknowledge it. And Bowie? He did more than just nod in our direction—he made space, he uplifted, and he spoke out when it mattered.

The Funk and Soul of Bowie: The Luther Vandross Connection

Let’s start with the big one: Luther Vandross. Yes, before Luther was THE Luther—the voice of smooth R&B seduction and the soundtrack to many a slow jam—he was singing backup for Bowie. And not just any gig, but on the 1975 album Young Americans, one of Bowie’s most Black-inspired records. The album itself was drenched in soul—proper soul, not just some watered-down version of what white executives thought soul music should be.

Bowie didn’t just bring Luther along for the ride; he listened to him. It was Vandross who came up with the vocal arrangements on Young Americans and who contributed to what would become the signature sound of that era of Bowie’s career. And Bowie, instead of pulling the usual “white rock star absorbs Black talent then moves on” move, actively pushed Luther forward.

Luther eventually left the backup singer life to become one of the biggest R&B stars of all time, but he never forgot Bowie’s impact. And Bowie? He never stopped singing Luther’s praises. Unlike certain people (looking at you, Elvis), Bowie didn’t just co-opt Black music—he collaborated, respected, and made sure his Black peers got their dues.

Station to Station: The Carlos Alomar Factor

Now, let’s talk about Carlos Alomar—a Puerto Rican guitarist who became one of Bowie’s most essential musical partners. When Bowie wanted to dive deep into funk and R&B, he didn’t just dabble; he surrounded himself with the best. Alomar co-wrote Fame (yes, the same Fame that would become Bowie’s first U.S. number-one hit), alongside John Lennon. And guess what? Unlike the usual Babylonian nonsense where the white artist gets all the credit, Alomar got his co-writing credit and secured his royalties.

And this wasn’t a one-off thing. Alomar became Bowie’s go-to guitarist for decades, playing on albums from Young Americans to Let’s Dance. The collaboration was deep, respectful, and—importantly—mutually beneficial. No exploitation, just straight-up artistry.

Bowie vs. Babylon: The MTV Interview That Shook the Table

Alright, let’s get to the real moment that cemented Bowie as an ally before the term was even a thing. In 1983, Bowie sat down for an MTV interview, and instead of the usual rock-star fluff, he flipped the script and asked why MTV wasn’t playing Black artists.

Picture it: early ‘80s, MTV barely playing any Black artists aside from the occasional Michael Jackson video (and even that was a battle), and here comes Bowie, a massive star at the peak of his fame, calling out the network on their own platform.

The interviewer, looking like he wanted the ground to swallow him whole, tried to stumble through some Babylonian excuse about “audiences in the Midwest not being ready for Black music.” And Bowie? Unmoved. Unshaken. He kept pressing, making it very clear that he saw what was going on and wasn’t here for the bullshit.

Now, let’s be real—Bowie didn’t have to do this. He could have sat there, promoted his album, and moved on. But he didn’t. He put MTV on blast in a way that few white artists of his stature ever dared to do. And in doing so, he helped push the conversation forward, forcing MTV to reckon with its exclusion of Black artists.

Let’s Dance… with Nile Rodgers

If you’ve ever danced to Let’s Dance, then you owe a debt to Nile Rodgers, the legendary producer and founding member of Chic. Bowie, wanting to reinvent his sound for the ‘80s, went straight to the source—the Black source. He didn’t want some watered-down version of funk; he wanted the real thing.

Rodgers didn’t just produce Let’s Dance—he revolutionised it. Bowie gave him free rein to reshape the sound, leading to one of the biggest albums of Bowie’s career. And again, we see the pattern: Bowie working with Black artists, not just taking from them.

So, What’s the Verdict?

Was Bowie perfect? Of course not. The man had his problematic moments (that Thin White Duke phase was a whole heap of madness). But when you step back and look at the bigger picture, you see an artist who engaged with Black music authentically, credited the people who helped shape his sound, and used his platform to challenge the industry’s racial biases.

Unlike so many of his contemporaries—who dipped their toes into Black music only to run back to whiteness when it suited them—Bowie stayed in the trenches. He built long-lasting collaborations with Black and POC musicians, fought against Babylonian bullshit when he saw it, and made sure his peers got the shine they deserved.

And that, my friends, is why Bowie deserves his flowers. Not because he was some white saviour, but because he understood that music—real music—isn’t about extraction. It’s about collaboration, respect, and knowing when to pass the mic.

#DavidBowie #DecoloniseMusic #GiveCreditWhereItsDue

Thanks for the tribute and the education. I knew nothing of Bowie besides, Let’s Dance, and The Hunger, his movie with Catherine Deneuve. Let’s Dance was just another MTV party song but the movie hit me viscerally. I can still feel the mood of it, his vulnerability and humanity. That movie made me take notice of him.

Wonderful to read that he was big hearted as well and gave black musicians their due.